Taylor Swift makes her own sunshine on “The Life of a Showgirl”

Over the course of her nearly two-decade career, Taylor Swift’s sly sense of humor and puckish nature has often gone overlooked or unnoticed by far too many critics and listeners alike. She’s turned a satirical eye toward her media portrayal as a “psycho serial dater girl” on the hit “Blank Space,” for instance, and poked fun at herself and her literary pretensions on the title track of last year’s The Tortured Poets Department.

That sense of humor is on full display on her latest album, the fun and brilliant The Life of a Showgirl. Light-hearted and sunny but neither lightweight nor pollyannaish, the album sees Swift shed her insecurities and anxieties to embrace the mischievous side of her personality amidst a catchy, upbeat mélange of 1970s vintage pop sounds that ranges from disco to folk to Fleetwood Mac-style rock over its taut, straight-to-the-point 42-minute runtime. All the while, she sacrifices very little if any of the emotional depth we’ve come to expect from her music; indeed, she maintains a laser-like focus on her lasting artistic preoccupations: resilience in the face of adversity, a love of fate, and the basic human desire for intimacy and connection. In that, she once again manifests her singular ability to transmute the intensely personal and idiosyncratic into the shared and universal.

Or as she herself puts it, her music serves as a mirror for her listeners that can reflect their own experiences at a given moment in their lives.

On The Life of a Showgirl, Swift is less interested in self-doubt and searching introspection—though it still quietly lingers on deep in the background—than in distilling and dispensing hard-earned wisdom. Life can be tough and often takes more than it gives, she reminds us, but it’s how we deal with the hardships and heartbreaks that inevitably come our way that really matters. No matter what happens, it’s up to us to make our own happiness and live life to its fullest regardless of our own circumstances or shared predicaments—and despite the physical and emotional pain that may be involved. It’s a sentiment that resists the rampant cynicism and nihilism of our time in the best possible way, shooting a piercing ray of light through the doom and gloom of an ever-darkening age.

But more on that later.

Album opener “The Fate of Ophelia” kicks off The Life of a Showgirl with a bang, an obviously self-conscious riff on Shakespeare in the vein of “Love Story.” Here, Swift once again inverts the tragic death of a lovelorn character driven to extremes by heartbreak. She finds herself saved from this fate by her new significant other (as well as the massive crowds that turned out for her monumental Eras Tour, if her written prologue is any indication), who “dug me out of my grave” and stopped love from driving her mad. “No longer drowning and deceived,” she intones quietly, “All because you came for me.” This sense of release comes across strong in the chorus, as she sheds the fears and worries that previously held her back.

The next track, “Elizabeth Taylor,” catches Swift in an anxious frame of mind as she reflects on her history of failed relationships and wonders hopefully if her present romance will actually last.1 “All the right guys promised they’d stay,” she laments, “Under bright lights, they withered away/But you bloom.” There’s something different about her current lover, though, and she warns him not to “ever end up anything but mine.” Thundering keyboard strikes and beats accompany Swift’s winding vocals and reflect her moody, ruminative lyrics. And she’s equally apprehensive about her staying power as an artist and performer: “You’re only as hot as your next hit, baby,” she reminds herself.

But it’s “Opalite” that’s both the standout song on The Life of a Showgirl and the album’s thematic crux. The track opens with a first verse that expresses Swift’s former anxiety: she persistently ruminated about past lovers, believed her house to be haunted by her past relationships, and worried that new ones were never going to last. Swift reaches back and reprises imagery and motifs from earlier songs like “Bejeweled” and “Daylight” as well as albums like folklore2 and Midnights; she and her significant other were once “Sleepless in an onyx night/But now the sky is opalite.” What’s more, they ought to appreciate the experiences that led them to where they are now. “It’s all right/You were dancing through the lightning strikes,” she reassures us.

An infectiously happy bridge lays out Swift’s overall philosophy of life quite nicely:

This is just

A storm inside a teacup

But shelter here with me, my love

Thunder like a drum

This life will beat you up, up, up, up

This is just

A temporary speed bump

But failure brings you freedom

And I can bring you love, love, love, love, love

Airy, dreamy guitar work and upbeat melodies complement Swift’s lyrics beautifully as she turns setbacks, hardships, and heartbreak into the path forward—not something to be avoided, but in fact embraced or, at least, accepted as a way to “make your own sunshine.”

The ancient Greek and Roman philosophical notion that the perfectly wise sage is content even under torture and other extreme, painful situations because he or she chooses to focus on what really matters suggests itself here: no matter our particular circumstances or experiences, we have the power to create our own contentment. Or as Swift herself explains, “life isn’t going to always give you what you want, you’re not always going to get your way, you’re going to get your heart broken, things are going to happen to you, chaos will ensue, but you have to pick your own happiness… You have to sometimes make your own happiness, just like man-made opal.”

If “Opalite” stands out as The Life of a Showgirl’s exuberant statement of purpose, “Eldest Daughter” and “Ruin The Friendship” together serve as its beating, bleeding heart. On the former track, Swift fires a broadside against online culture and ironic detachment before launching into an encomium to sincerity and vulnerability. Fashionable poses of apathy ring hollow, and Swift no longer feels the need to practice “cautious discretion” in an effort to seem unbothered—she’ll stick with her own innate earnestness instead. A delicate piano and acoustic guitars set a confessional mood as Swift reclaims the innocence and idealism of her childhood over a killer bridge: “I thought that I’d never find that/Beautiful, beautiful life that/Shimmers that innocent light back/Like when we were young.” With her vow to never leave or let down herself, her significant other, and everyone else who matters in her life, she exposes her own personal vulnerabilities and gives us license to to the same—even at the risk of appearing uncool and out of step with the pervasive cynicism of our times.

In “Ruin The Friendship,” Swift paints a striking and heartfelt portrait of a youthful romantic risk not taken. Set to a bouncy 1970s-style bass line, it’s a classic Swift story that’s shot through with evocative detail through the two first verses: “Glistening grass from September rain” as she and her friend speed down Tennessee roads, for instance, while a “Wilted corsage dangles from my wrist” at prom. A quietly devastating emotional blow follows the bridge: “Abigail called me with the bad news/Goodbye/And we’ll never know why.” “My advice is to always ruin the friendship/ Better that than regret it for all time,” Swift counsels as the song climaxes, “And my advice is to always answer the question/Better that than to ask it all your life.” Take advantage of the present moment, she urges, live life to the fullest in the here and now—and don’t dissuade yourself from taking risks out of an irrational fear that the worst might happen.

Swift goes fully tongue-in-cheek with several irreverent and playful tracks on the back half of The Life of a Showgirl. Over an edgy guitar riff on “Actually Romantic,” she springboards off specific incidents to craft a wider critique of her detractors—but more importantly, Swift artfully reframes the vitriol she receives as a strange form of endearment rather than believing it should leave her upset. “It’s honestly wild/All the effort you’ve put in,” she says, marveling at the time and energy others devote to disparaging her. (The dictum of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus that it’s not things themselves that disturb us but our opinions about them comes to mind.) The song also lays a clever trap for its supposed targets and Swift’s other would-be backbiters and denigrators: if they respond in any real way, they simply prove her underlying point.

Then there’s “Wood,” a cheeky disco-inflected number that starts innocently enough as Swift declares she’s done with superstition when it comes to romance; she and her partner now make their own luck. The song then dramatically swerves into sexual innuendo about as subtle as Prince’s on the likes of “Head” and “Erotic City.” Swift proclaims (among other things) that she doesn’t need to catch a wedding bouquet to “know a hard rock is on the way.” It’s a legitimately hilarious song, and deliberately so—as on all her songs, she knows exactly what she’s doing here.3

For its part, “CANCELLED!” weaves satire and serious reflection together as Swift laughs at and learns from her own experience of unwarranted social death, gently teasing her reputation era persona while offering counsel to anyone who might confront similar predicaments. She enumerates the petty pretexts often put forward for cancellation and notes just how quickly a mob mentality takes hold; aspiring cancelers have “already picked out your grave and hearse,” and there’s nothing much to be done about it. As the song proceeds, however, Swift stresses the need for resilience in the face of unjustified opprobrium and ostracism: “Now they’ve broken you like they’ve broken me/But a shattered glass is a lot more sharp/And now you know exactly who your friends are/We’re the ones with matching scars.”

It’s an arch lyric: Swift wasn’t broken by her attempted cancellation but, as she makes clear, emerged stronger for all its torment.3 The seemingly worst experiences can, in fact, leave us better off—the most difficult obstacles we face can become the way forward if make proper use of them.

After the sweet and endearing palate-cleanser “Honey,” The Life of a Showgirl concludes with a stirring, valedictory title track that reminds us of the pain and hardship that’s typically involved in doing anything worthwhile—especially in light of the grueling nature of Swift’s own Eras Tour. She and pop starlet Sabrina Carpenter trade verses about an encounter with an experienced entertainer who tries to discourage their dreams of a career in show business. The song steadily escalates to a cathartic bridge, where Swift proudly declares she “took her pearls of wisdom, hung them from my neck/I paid my dues with every bruise, I knew what to expect.” She’s now “married to the hustle” and will “never know another” life outside of the one she’s got—and she “wouldn’t have it any other way.” An outro featuring audio from the end of the Eras Tour puts an exclamation point on the album: pain in life and show business is real, but damn if it isn’t all worth it.

As an album, The Life of a Showgirl has many more layers to peel back, from Swift’s never-ending dialogue with her earlier work and her addictive, purposeful wordplay to the album’s literary conceits and its commentary on the destructive power of social media. Indeed, Swift’s ability to layer meanings and motifs one on top another—all without contradiction—is part and parcel of her particular genius as an artist and songwriter.

Beyond all that, though, The Life of a Showgirl runs directly against the dark and dismal temper of our times—and in the best possible way. Swift has never shied away from vulnerability and emotional sincerity in her music, and this album in particular marks perhaps her most sustained assault yet on the ironic detachment and cynicism that have pervaded and corroded our public lives and personal relationships over the past decade. We live in an era steeped in nihilism, after all, one that gives free rein to our basest instincts and dissolves the bonds that join us together as fellow citizens and, indeed, human beings.

Given this sordid state of affairs, it’s all too easy to assume that we ought to remain moody and angry and joyless lest we fail to take our situation seriously enough—as if drowning ourselves in that cocktail of misery, rage, and despair known as doomerism somehow keeps us vigilant against the encroaching darkness. That’s not a knock against music and other forms of art that express whatever angst and fury we may feel about our ongoing slouch toward fascism, but simply to observe that we already have a surfeit of such material available at the moment. More to the point, though, it’s essential for our own sanity in present circumstances to refuse the temptation to confine ourselves to one single suite of emotions.

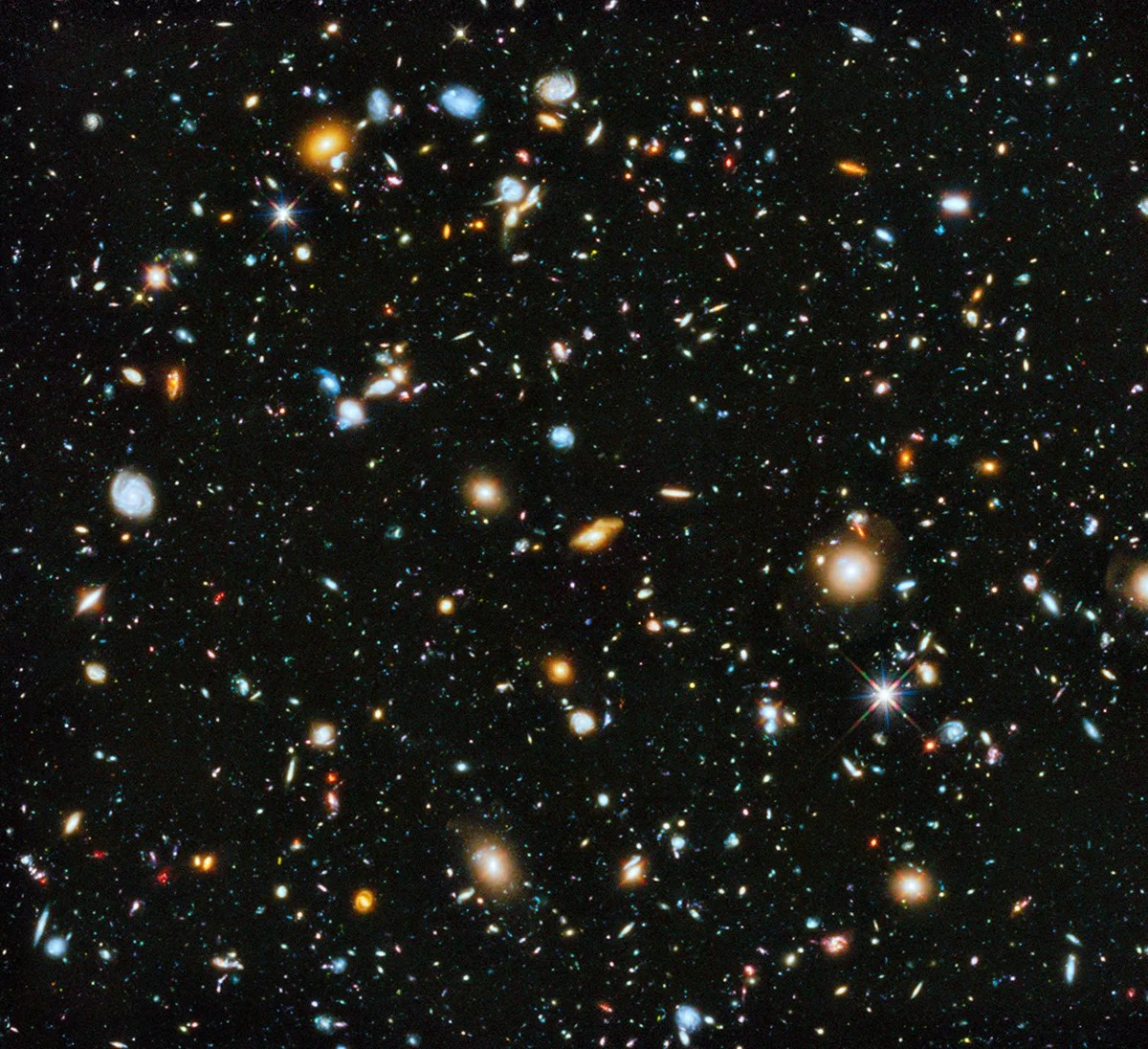

With The Life of a Showgirl, Swift tells us to take and feel whatever joy and happiness we can make for ourselves and others—especially those closest to us—even as the world falls apart around us. It’s a bright and shiny antidote to the nihilism and doomerism so prevalent today, a stark contrast to the supermassive moral black hole that is the current presidential administration and the pessimistic, nothing-matters zeitgeist it engenders among too many of its erstwhile opponents. That contrast makes the album and indeed Swift herself strangely countercultural by default, despite her own status as the one mainstream pop culture icon whose albums still sell in the millions.

If nothing else, The Life of a Showgirl provides the sort of re-energizing jolt that many of us need right now—a reminder that we retain the ability to make our own sunshine, no matter how dark things may get in the world. And that’s no small feat these days.

- Elizabeth Taylor, it should be noted, became known for her multiple failed relationships as much as her career as an actor—making her a source of advice for Swift as she ponders her own serial romantic failures and strikes out for a new relationship she hopes will last. ↩︎

- The contrast with folklore’s “peace” is striking and noteworthy: on that track, Swift plaintively asks her then-significant other if it’d be “enough if I could never give you peace?” Now, however, Swift confidently offers her new partner shelter as the storms rage around her—it’s no longer a question, but an assertion. ↩︎

- It’s made all the funnier by the attempts by Swift and fiancé Travis Kelce to insist with barely straight faces that the song is not at all about what we all know it’s obviously about, at least in part. ↩︎

- It’s also an intriguing echo of a lyric from folklore’s “mirrorball,” where masked partygoers “watch as my shattered edges glisten” after she breaks into “a million pieces.” And Swift’s own proclaimed artistic ambition for her work “to be a mirror for people” reflects the song’s conceit of Swift herself as a mirrorball who will “show you every version of yourself tonight.” ↩︎